New London Architecture

Technical Explainer: Building performance

Tuesday 09 May 2023

Building performance is a broad term, covering a variety of aspects which can have different meanings, depending on who you ask.

When I talk about building performance, I’m thinking about a building which really works for the occupants, offering spaces which allow them to thrive in terms of their comfort, health and wellbeing, and uses the least amount of energy possible. Just as important is how the building and its facilities meet the occupants’ needs, whether its playing sport, working and collaborating with colleagues, watching a play, or simply having a good night’s sleep. Given the necessary drive towards net zero carbon, it is unquestionably vital to deliver buildings which touch lightly, emitting as little carbon as possible during their operation.

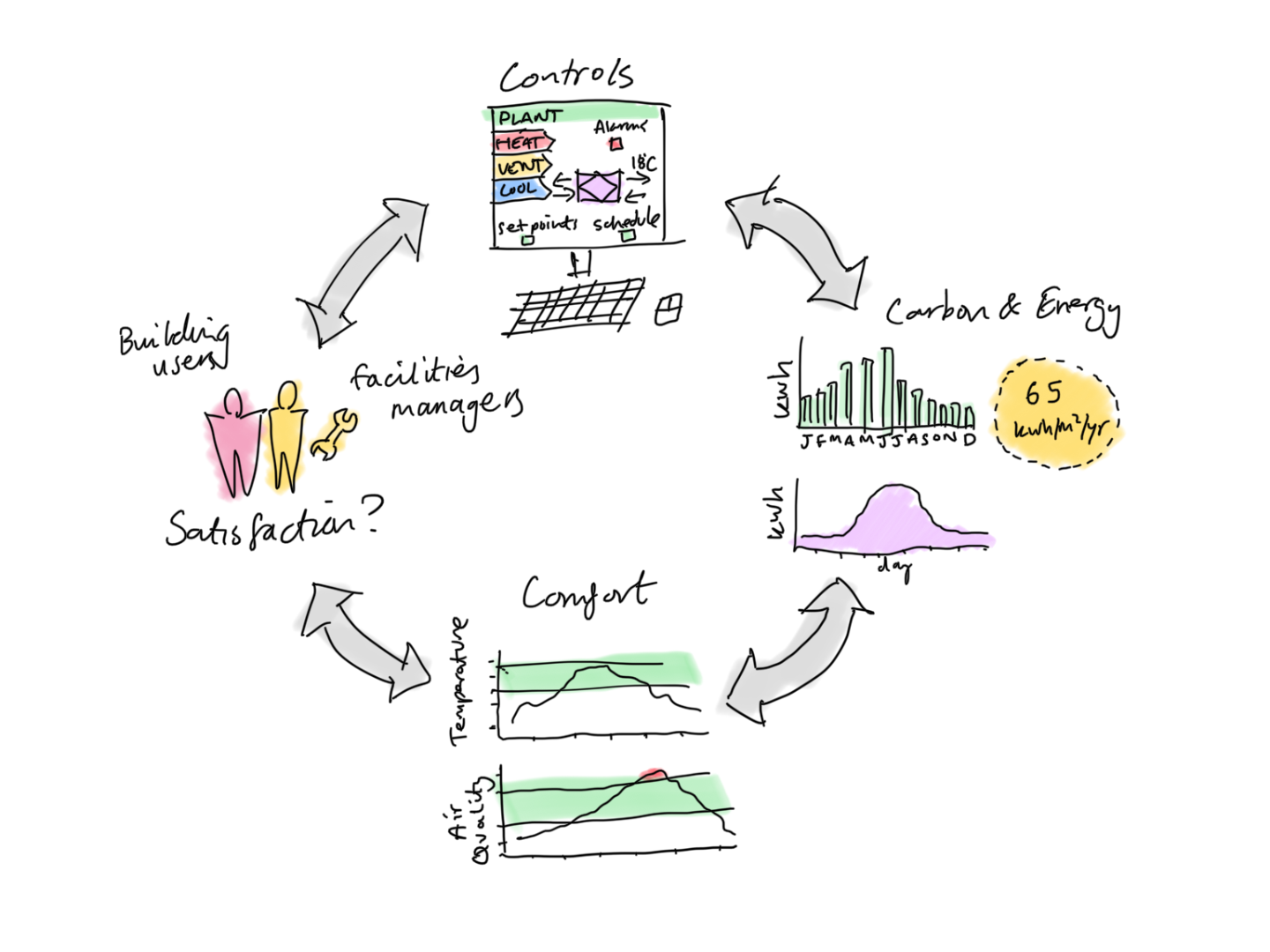

The question is, how do we really know if a building performs well? To find this out we need to visit the building and collect information on building performance metrics to verify its performance. This is a process often known as Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE), which is understanding buildings and how people use them. Measurement techniques include collecting energy consumption data, gathering feedback from the building users, and ideally gathering information on internal environmental conditions.

In practice, it’s certainly possible for an energy efficient building, and one which uses almost no energy for heating in winter, to be an unenjoyable space for occupants. There can be several reasons why a building might not be a comfortable environment, for example, it might be significantly under-ventilated, evident from elevated internal CO2 levels, indicating poor air quality. If this were the case, revealed by air-quality analysis, the next step would be to try and rectify the situation. This is not always straightforward as it often requires an understanding of the design intent, what has been delivered on site, and how the building is being run and operated.

One key driver of building performance that should not be underestimated, is how the building is being run and managed. Facilities management teams are often instrumental in achieving high performance – of course, in a domestic setting, the facilities team is essentially the home occupier! Things can go awry if the controls within the building don’t allow users to operate the building as intended. In a commercial setting this is often the building management system (BMS) which requires careful specification, commissioning and user training to get the most out of it. I think we’ve all had experiences of homes with heating thermostats that are far too complex to understand. Scale this up to large estates where the energy consumption is vast and there’s potential for a lot of energy to be wasted. Keeping the controls simple and intuitive is always important, no matter what the building type.

It’s really positive to see the industry moving towards adopting measurable operational energy targets on projects with measured outcomes being much more of a focus. This work has been championed by LETI and RIBA and is moving forward as part of the Zero Carbon Buildings standard. Soft Landings is a useful process to help increase the likelihood of achieving these operational energy targets. This places increased emphasis on setting up the building to achieve low energy outcomes right from the inception and ensures key members of the design and contractor teams stay involved during a 2-3 year aftercare period of POE and building optimisation.

Staffordshire University Catalyst Building is a good example of a project that is currently on track to achieve ambitious energy targets after the first year of operation. We have been reviewing the building performance during its first year, with the contractor team engaged as part of the Soft Landings aftercare process. This project has benefited from an excellent and engaged building controls specialist, together with an energy management software package, allowing in-depth insights into when and where energy is being used. This data has helped justify decisions around how to manage and control the building, ensuring occupant satisfaction is balanced while keeping energy consumption as low as possible.

Images below:

1. The Building Performance process. Copyright Tom McNeil/Max Fordham

2. Staffordshire University Catalyst Building, Copyright Daniel Hopkinson

Images below:

1. The Building Performance process. Copyright Tom McNeil/Max Fordham

2. Staffordshire University Catalyst Building, Copyright Daniel Hopkinson

Recent

News

Five minutes with... Jack Hawthorne

David meets Henley Halebrown associate and former RIBA Rising Star Jack Hawthorne to talk workload, international compet...

News

Gateways to Whitechapel Shortlisted Designs Revealed

Introducing the shortlisted designs for the 'Gateways to Whitechapel' design competition, now open for public feedback a...

News

Preparedness, Not Prediction: Hawkins\Brown x NLA Foresight Roundtable

Jess Beaumont of Hawkins\Brown Ltd explores how foresight helps long-term asset holders plan resilient, flexible places...

Stay in touch

Upgrade your plan

Choose the right membership for your business

Billing type:

Small Business Membership

£90.00

/month

£995.00

/year

For businesses with 1-20 employees.

Medium Business Membership

£330.00

/month

£3,850.00

/year

For businesses with 21-100 employees.

View options for

Personal membership